Approaching pediatric patients as partners in care was the theme of a collaboration between Megan Denham, a senior research associate at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI), and doctors at the Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. In fact, it was part of the title: “Designing Cancer Care For Kids, By Kids,” where children receiving chemotherapy helped researchers collect quantitative and qualitative data about their visit to the clinic.

Often pediatric cancer patients go through a complicated process in which they see multiple providers for different procedures in different rooms. The kids used a “passport” that was stamped by members of their care team at each step of their treatment. They also wrote and colored in the passport to let researchers know how they were feeling along the way. In essence, said Denham, researchers then had access to the best, but often overlooked, source of information: the patients themselves.

Identifying inefficient processes and long wait times, along with opportunities for improvement in the built environment — like more electrical outlets for parents who spend all day in the clinic with a child — was an important part of the study. So was understanding where and why the kids felt unhappy or scared. “One of the most striking findings was that the locations where they spent the most time were also the places they reported the most negative emotions,” said Denham.

Based on what the kids said, the clinic has already begun to make some changes in its processes and even its physical environment. For example, one thing the researchers heard was that kids wanted “fewer pokes.” Karen Wasilewski-Masker, who is the center’s medical director, a pediatric hematologist, and a champion of the project, found they could reduce the number of blood draws. And after hearing a 12 year old express a desire for “a private bathroom where I could throw up in peace,” Wasilewski-Masker asked architects of their new hospital unit to put more bathrooms in the rooms.

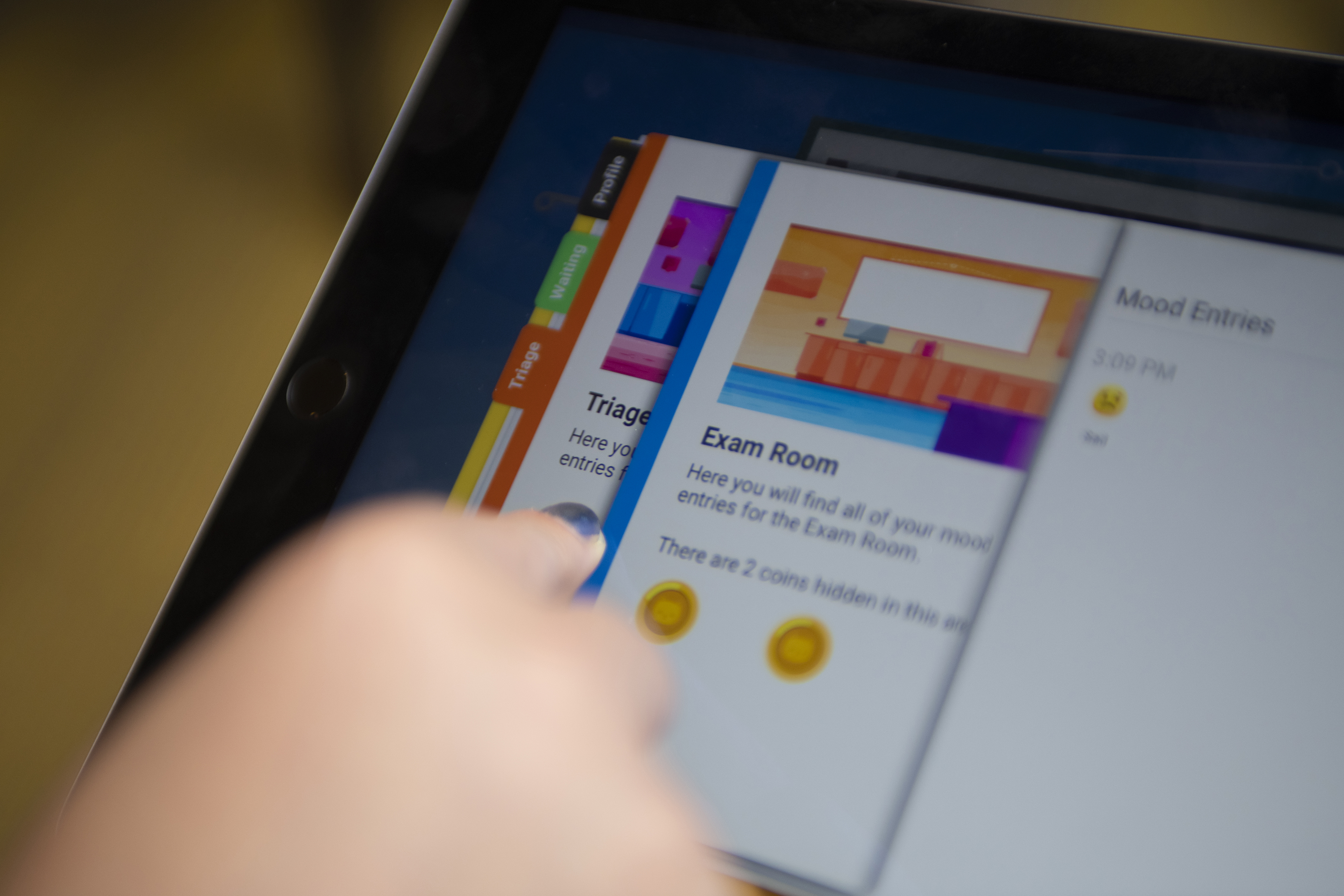

The first passport was paper-based and supported through the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta Pediatric Technology Center. Now with additional funding from the Imlay Innovation Endowment Fund at Children’s, established to foster collaboration between Children’s and Georgia Tech, Denham’s team is working on an app that would have additional functionality.

For example, at the Aflac Survivorship Clinic, children may move not only from room to room but facility to facility. “They may go upstairs to get an echocardiogram, across the street to get a PET scan,” Denham said. “It would be difficult to track that on paper.” Ideally, the app could be flexible enough to use in other clinics and pediatric hospitals.

The idea for the project came from one of Wasilewski-Masker’s patients, Kiersten, who spoke to an evidence-based design class at Georgia Tech a few years ago and talked about her experiences and the many things she couldn’t control. That encouraged Denham and her team to think about solving problems with patients instead of for them. “Every time we would get stuck on something, we would remember, ‘We need to ask the kids,’” she said.

Unfortunately, not all pediatric cancer patients survive; Kiersten died before her 21st birthday, and in some ways, Denham sees the project as her legacy. “We keep in touch with her family and let them know what we’re doing, and they know Kiersten is the one who inspired all of this work,” she said. “I think that kind of legacy is important for families when they are robbed of a life that has barely begun.”

This article was excerpted from a longer feature on pediatric technology research published in Georgia Tech’s Research Horizons magazine. To read the complete article, please follow this link. http://rh.gatech.edu/features/think-small