A small spacecraft assembled and tested at the Georgia Institute of Technology is on its way to the moon, where it will use lasers to search for surface water ice in lunar craters that are never warmed by light from the sun.

The briefcase-sized Lunar Flashlight will be monitored and controlled over the next several months by a team of graduate and undergraduate students in Georgia Tech’s School of Aerospace Engineering. The team will keep the spacecraft on track and capture the data it gathers to be studied by the Lunar Flashlight Science team.

Watch a video on the Lunar Flashlight mission on YouTube

The spacecraft launched at 2:38 a.m. December 11 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket that also carried a Japanese-built lunar lander and a United Arab Emirates rover. Shortly after launch, Lunar Flashlight separated from the Falcon 9 to begin an approximately three-month journey that will carry it into a fuel-conserving orbital trajectory 42,000 miles beyond the moon. Gravity from the moon, Earth, and Sun will ultimately bring it into a path that will come within nine miles of the lunar surface.

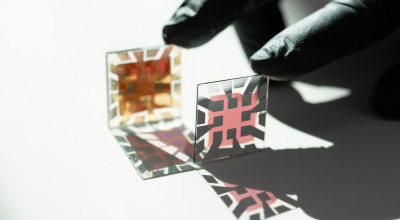

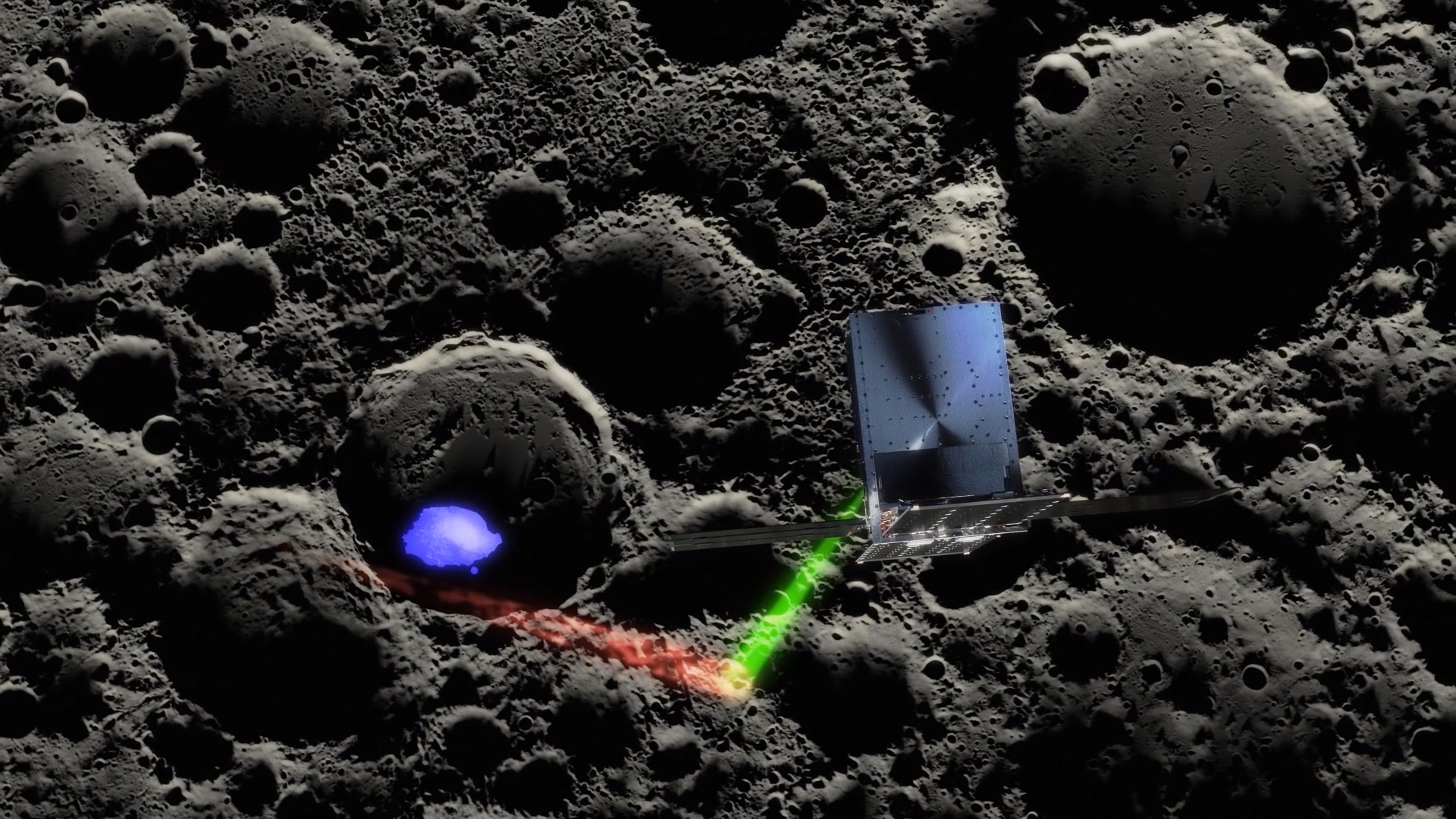

Once in its science orbit around the moon, Lunar Flashlight will shine four lasers into perpetually-dark craters near the lunar South Pole. Each laser operates at a slightly different frequency, and the reflected light acts like a spectral fingerprint that identifies the material that it illuminated. If ice is there, the near-infrared light from the lasers will be absorbed by the water. If the light reflects back to the Lunar Flashlight, that will indicate the absence of ice. Data from the spacecraft will be radioed to NASA’s Deep Space Network and received by student controllers on the Georgia Tech campus, who will then share it with the Lunar Flashlight Science Team.

Surface water ice may be a treasure trove of water from different sources such as volcanic outgassing and meteorite impact, so knowing where it resides will help point future assets to examine it at the surface. If sufficient amounts exist, the precious liquid may be used to help meet the drinking water needs of future lunar colonies. Water molecules from potential ice reservoirs in the South Pole craters could also be split to provide a source of oxygen for breathing and hydrogen for rocket fuel.

Big Capabilities in a Small Spacecraft

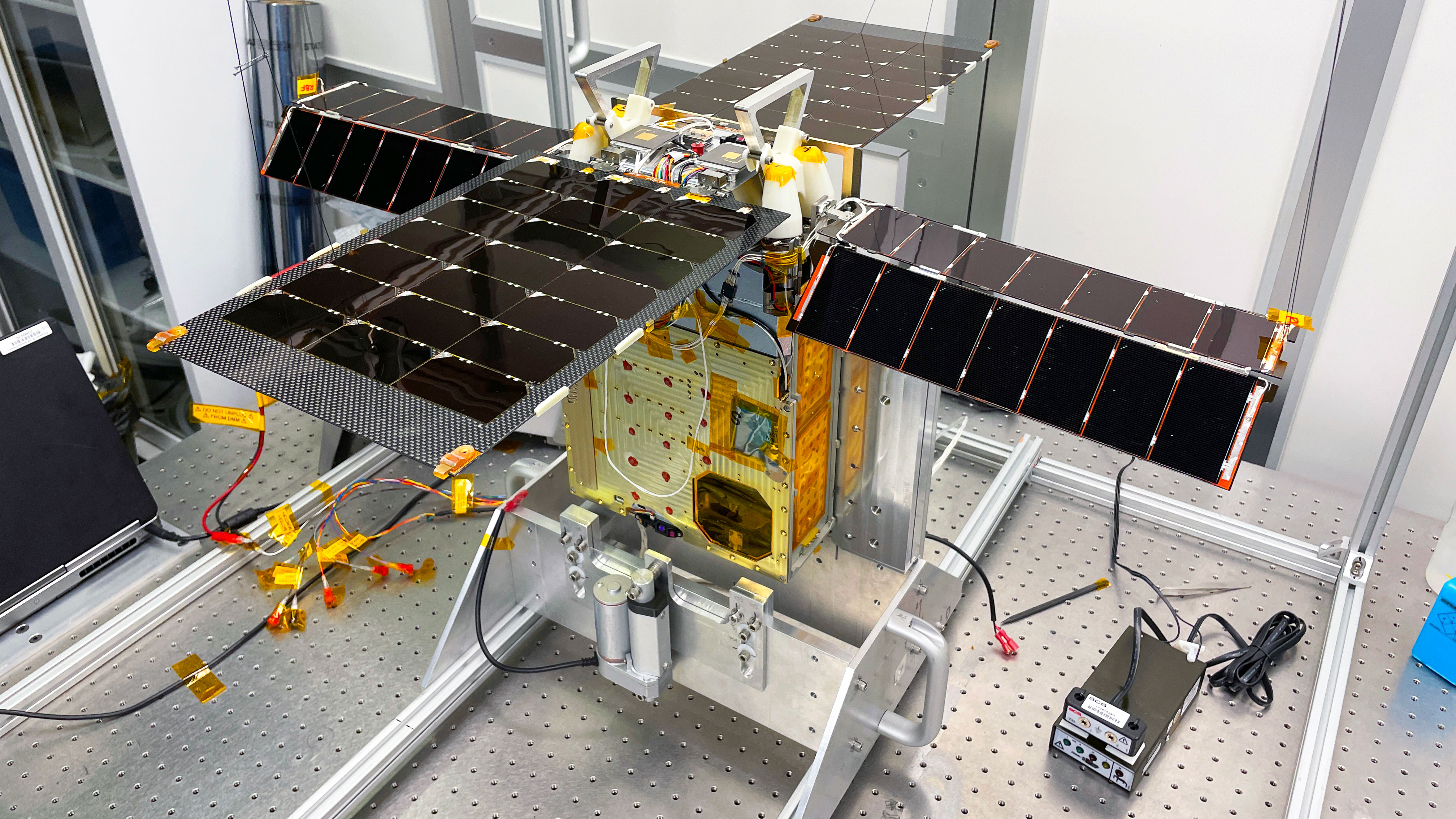

Despite its small size, Lunar Flashlight – which was designed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory – has big capabilities. Lunar Flashlight carries a propulsion system that will be used to make mid-course corrections and allow the spacecraft to get into lunar orbit and accomplish its mission. Built at Georgia Tech’s School of Aerospace Engineering, the propulsion system uses a new monopropellant developed at the Air Force Research Laboratory to be more environmentally safe than earlier propellants.

“It’s a very capable spacecraft for sure,” said Jud Ready, a Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) principal research engineer who served as principal investigator for the final assembly and testing of Lunar Flashlight at Georgia Tech. “Achieving lunar orbit insertion can be challenging for a conventional spacecraft, let alone a vehicle the size of a desktop computer.”

The solar-powered Lunar Flashlight is part of a new generation of small spacecraft with capabilities formerly seen only on larger vehicles. First used in low earth orbit, the smaller vehicles are now traveling to the moon, and potentially to other planets in the solar system.

“Space exploration was formerly the realm of major governments – the United States, Russia, China, Japan, and a few others,” said Ready. “Using smaller spacecraft like Lunar Flashlight means a lot more opportunity for this. There will likely be thousands of other small spacecraft launching behind us.”

A Learning Experience for GTRI and Georgia Tech

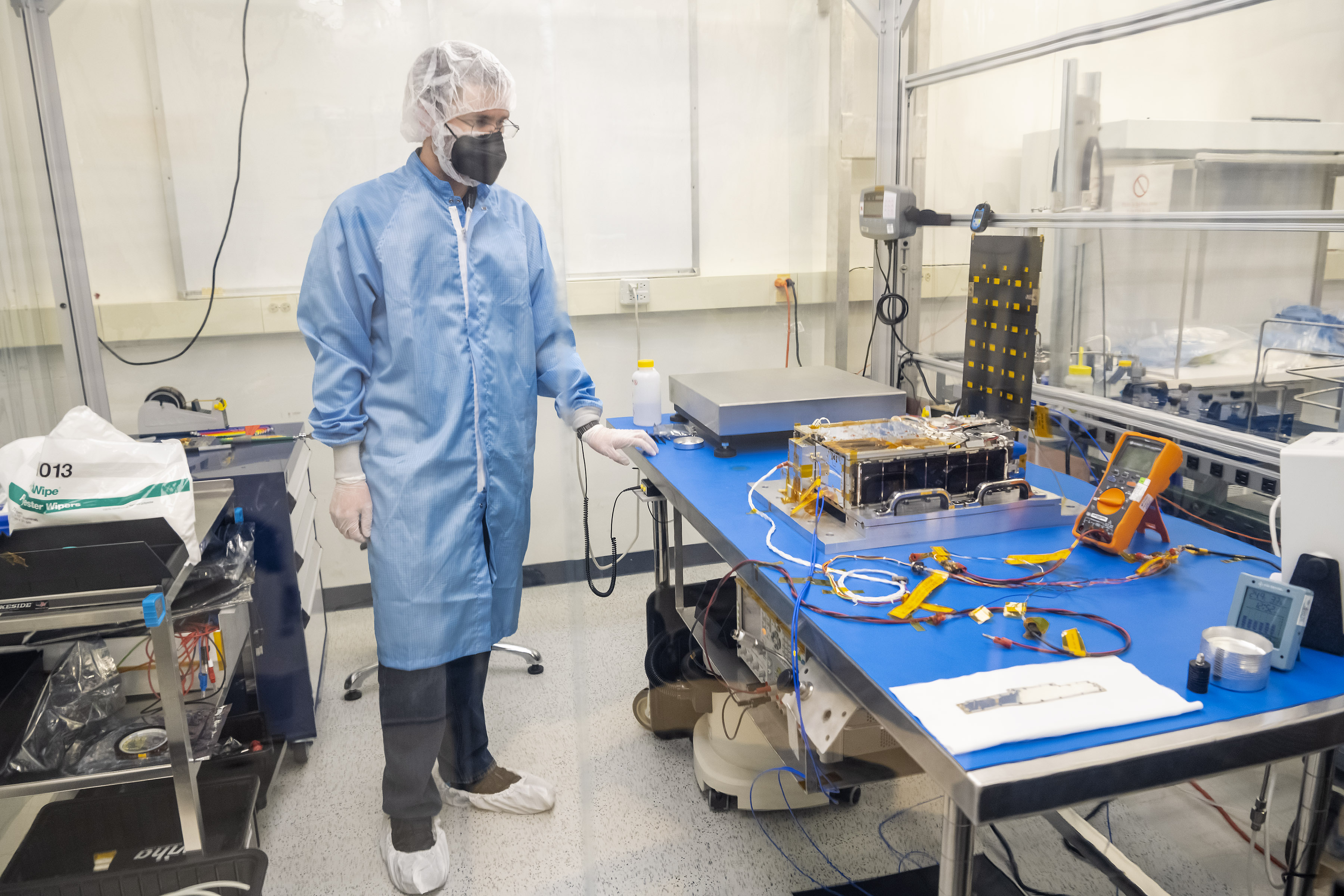

Final assembly of the Lunar Flashlight took place in a cleanroom in a GTRI building on the main Atlanta campus, where the laser system also was tested. Specialized equipment at GTRI’s Cobb County Research Facility tested the spacecraft’s radio equipment and simulated the stresses of launch. Thermal, vacuum, and other testing took place in Georgia Tech’s School of Aerospace Engineering.

For the faculty, staff, and students involved, Lunar Flashlight has provided a great learning experience.

“We learned how to apply NASA’s rigorous protocols to everything we did, protect the spacecraft from electrostatic discharge, schedule complex testing tasks, and utilize our student researchers who must also maintain their schoolwork and take exams,” Ready said. “There have been some real sacrifices by a lot of folks who worked long and odd hours.”

After completion of the final assembly and testing at Georgia Tech, Lunar Flashlight traveled to the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for fueling and additional testing. Finally, it made the trip to the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida for integration onto the SpaceX rocket.

Ready is hopeful that if Lunar Flashlight finds evidence of significant ice deposits on the moon’s South Pole, the precious water will help set the stage for creating a permanent human presence there.

“It’s really disappointing that we went to the moon in the 1970s, but didn’t stay there,” he said. “However, when you look at the big scheme of things, exploration is often measured in hundreds or even thousands of years. So, it’s not surprising that colonization of the moon would take longer than a few decades.”

Writer: John Toon (john.toon@gtri.gatech.edu)

GTRI Communications

Georgia Tech Research Institute

Atlanta, Georgia USA

MORE 2022 ANNUAL REPORT STORIES

MORE GTRI NEWS STORIES

The Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) is the nonprofit, applied research division of the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech). Founded in 1934 as the Engineering Experiment Station, GTRI has grown to more than 2,800 employees supporting eight laboratories in over 20 locations around the country and performing more than $700 million of problem-solving research annually for government and industry. GTRI's renowned researchers combine science, engineering, economics, policy, and technical expertise to solve complex problems for the U.S. federal government, state, and industry.