As music distribution technology shifted from analog vinyl records to digital compact discs (CDs) and then to streaming files, the sound quality took a substantial hit – along with the monetary value of the musical consumer product.

Now, as the vinyl format is enjoying a comeback, materials scientists at the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) have worked with a team of artists and recording engineers to boost the quality of analog music reproduction through a new surface coating that both improves sound quality and prevents wear. The patented technology led to the creation of a one-of-a-kind Bob Dylan record that recently brought $1.8 million at a Christie’s auction.

A First for a New Generation of Discs

The studio recording of Dylan’s 1963 classic “Blowin’ in the Wind” is the first of a new generation of unique archival records with spectacular sound quality and the capacity for a thousand plays (or more) without deterioration. For musician and producer T Bone Burnett, the goal of the effort was to provide musical artists with a new medium – and an opportunity to set the value of their work themselves.

“Recording artists have had the value of what we do determined for us under the shorter and shorter-term technologies of mass production and distribution by organizations, governments, distributors, streamers, and others, but we have not had a way to find the value of an individual work of art,” said Burnett, a long-time Dylan collaborator who played guitar on the recording. “If we are able to help establish a music space in the fine arts through the making of these archival discs, musicians will be able to find real value for their work.”

T Bone Burnett with a NeoFidelity Ionic Original disk. Photo: Jason Myers. Source: Christies.com

Nanometer-Scale Coatings Improve Quality

The new record format, which Burnett has dubbed an “Ionic Original,” was made possible by a unique coating of sapphire and quartz applied to a layer of nitrocellulose on an aluminum disc. The coating was developed with help from GTRI materials scientists Jud Ready and Brent Wagner.

“We helped them develop a way to put a hard oxide coating on top of the nitrocellulose lacquer to protect it during play,” said Ready, a GTRI principal research engineer and deputy director of Georgia Tech’s Institute for Materials. “That includes silica (SiO2), better known as quartz, and alumina (Al2O3), which is known as sapphire. With other ingredients and variables, it’s a gradient designed to produce the best sound quality and resist the wear that would otherwise happen to the nitrocellulose acetate.”

A hard coating is needed because the stylus “needle” used to play the record on a conventional turntable can be made of diamond, which is even harder than quartz or sapphire. Playing a traditional vinyl record causes abrasion in the much softer grooves where the music is stored, causing wear that degrades the sound quality over time and also creates annoying pops and noise – issues that led to adoption of compact discs which are played with a non-contact optical reader.

The NeoFidelity Ionic Original acetate disc of a 2021 recording of ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ with custom walnut and white oak cabinet sold for £1,482,000 on 7 July 2022 at Christie’s in London. Photo: Christies.com

The Analog Advantage

But digital formats used for consumer music recordings – CDs and streaming files – provide listeners a digitally sampled version of the original analog sound rather than more fully reproducing what was created by the musicians. This difference in acoustic reproduction helps account for the renaissance of analog records among audiophiles, and consumers in general.

“Analog music travels in actual waves – not sampled and simulated – and sounds more resonant, deeper, and truer,” Burnett explained. “Analog records more atmosphere. It is closer to the human. An Ionic Original is the equivalent of a painting, hand-made and retouched by the artist. A digital stream is the equivalent of seeing a copy of a photograph of a painting.”

Subjecting the Research to the Turntable Test

In 2013, Ready and Wagner worked with Burnett and recording engineer Barak Moffitt to develop the coating technique, which was patented. The patent is now owned by Ionic Recording Company LLC, which bought it from Georgia Tech. Separate from the original work that led to the patent, Ready more recently worked as a private consultant with Ionic to support refining the new process and identifying a company that could coat the record.

“The issues were in the thin film coatings – the time, the density of the coating, the ratio between the two elements – and the pre-cleaning process before the coating was put down,” Ready explained.

Ahead of the quartz-sapphire coating process, production of the record proceeded much like any other analog record. Dylan recorded the song in 2021; it was mixed in Los Angeles and Nashville, and finally mastered in Memphis by Jeff Powell, one of the world’s top vinyl cutting experts.

“When an artist like Bob Dylan, a producer like T Bone Burnett and a recording engineer like Mike Piersante went into a project like this, they knew the desired result was a pristine vinyl master lacquer that would go through the Ionic coating process and sound as good or better than any vinyl record ever made even after 1,000 plays,” said Powell.

Several 10-inch-diameter discs were made and compared by Piersante, who graded them all on a scale of zero to 10. The best one was sent to Virginia-based Blue Ridge Optics for application of the thin-film coating. After that, the disc flew by private jet to California, where it was analyzed acoustically and presented to the media. Finally, it went on to London for the Christie’s auction.

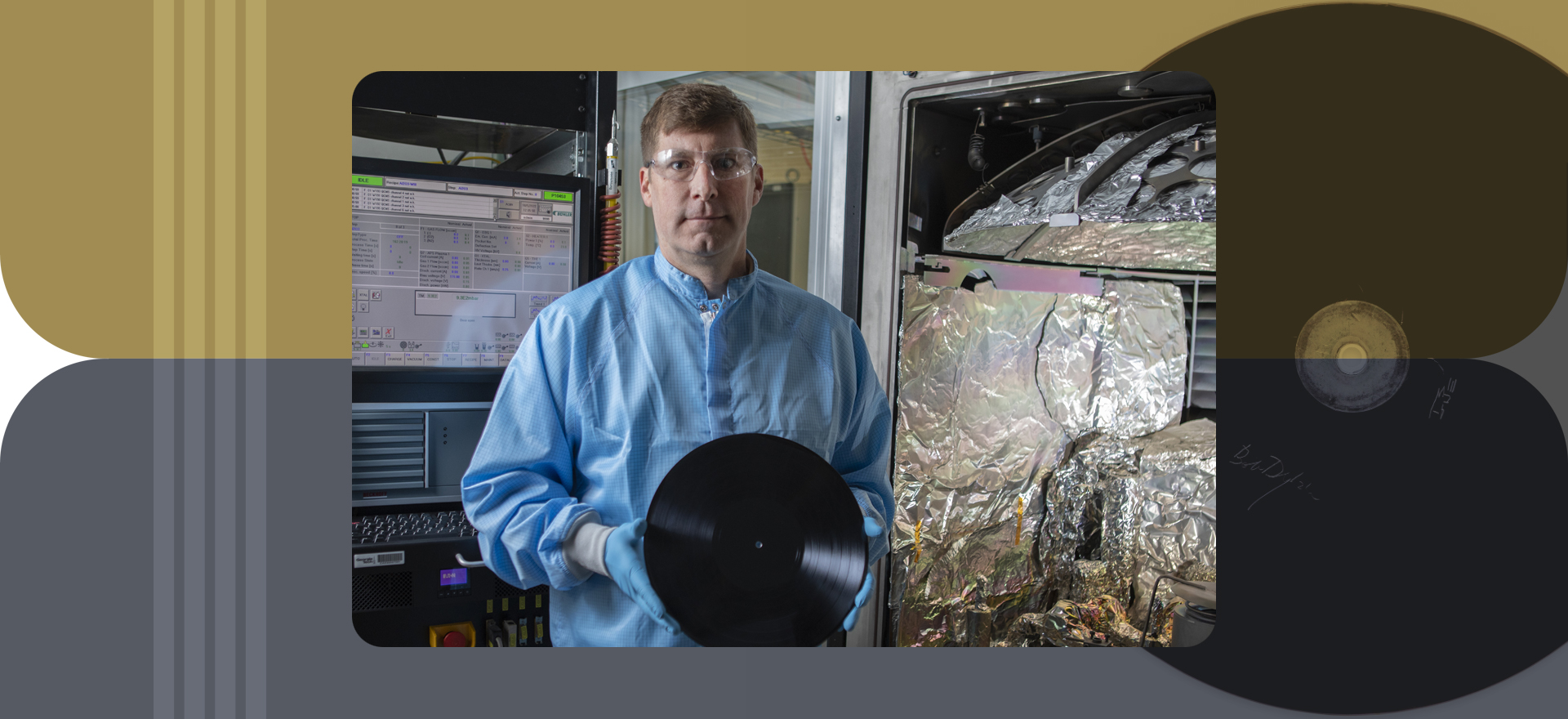

GTRI researchers used this equipment to apply wear-resistant coatings. Shown is Jud Ready holding an acetate of the type used in the research. Credit: Christopher Moore

An Eye-Opening Experience for a Materials Engineer

Ready’s bread-and-butter research involves thin-film coatings, but this is his first foray into the entertainment industry.

“We would normally put these down for optical coatings and to protect microelectronic devices,” Ready explained. “It’s a hundred nanometers or so of silica and alumina – a nanometer is a billionth of a meter – to create the scratch-resistant coating. At GTRI, we apply these coatings with a commercial-scale tool that is commonly used to put anti-reflective coatings on eyeglasses and on equipment used in space.”

Working as a consultant, Ready visited Burnett’s studio to compare the sound of the same song played from magnetic tape, vinyl, CD and finally, streaming files.

“The amount of resolution that goes away is incredible,” he said. “Whole instruments disappear. You could hear the faintest of different sounds on the tape and vinyl – but they were gone. There are ways that the CD recording is taking the sinusoidal analog waves and breaking them into lots of little rectangles. No matter how skinny you make the rectangle, you are always going to be losing some sound or adding noise.”

Jud Ready, a GTRI principal research engineer, worked with a team of artists and recording engineers to boost the quality of analog music reproduction through a new surface coating that both improves sound quality and prevents wear. Credit: Christopher Moore

“Blowin’ in the Wind” Could Make New Waves

The 2021 Bob Dylan recording of “Blowin’ in the Wind” was just the second ever to be made in the studio. Written by the artist in 1962 and released on The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan in 1963, it is a protest song that asks a series of questions about peace, war, and freedom. The song has been inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame and, in 2004, was ranked 14th on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the "500 Greatest Songs of All Time."

What’s next for the process? Burnett believes the technique may generate interest among music archivists who may want to store recordings protected from wear. He promises there will be more one-of-a-kind records, including “several” additional Dylan cuts.

“We are speaking with interested people about private sales, and with other artists about making further Ionic discs,” he said. “Perhaps there will be other auctions. We remain open to seeing where this path leads.”

Writer: John Toon (john.toon@gtri.gatech.edu)

GTRI Communications

Georgia Tech Research Institute

Atlanta, Georgia USA

MORE 2022 ANNUAL REPORT STORIES

MORE GTRI NEWS STORIES

The Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) is the nonprofit, applied research division of the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech). Founded in 1934 as the Engineering Experiment Station, GTRI has grown to more than 2,800 employees supporting eight laboratories in over 20 locations around the country and performing more than $700 million of problem-solving research annually for government and industry. GTRI's renowned researchers combine science, engineering, economics, policy, and technical expertise to solve complex problems for the U.S. federal government, state, and industry.